Update 2017-04-30:

Since my laptop became more or less impossible to use with the WD15 dock and multiple external monitors, I had to continue looking for a solution. First I spent the better part of Saturday to try to create a Windows To Go installation on a USB stick in order to run the WD15 firmware upgrade (that only works on Windows). After several failed attempts I looked elsewhere for a solution. Turns out that for any 16.04 LTS installation, kernel upgrades are held back, so while a fresh install of 16.04.2 from CD would give you a Linux 4.8 kernel, systems like mine that had 16.04 from start, would still have a 4.4 kernel, the reason is that pretty much the only reason for upgrading the kernel these days is to get better hardware support System that works fine with 4.4 will not get any benefits from an upgrade. But my system wasn’t working fine and the releases between 4.4 and 4.8, there has been a lot of Dell specific improvements and a bunch of usb-c improvements that could potentially make things better.

First, make sure you have all relevant upgrades so that your current system is in fact a 16.04.2.

erik@erik-xps ~ $ cat /etc/lsb-release DISTRIB_ID=Ubuntu DISTRIB_RELEASE=16.04 DISTRIB_CODENAME=xenial DISTRIB_DESCRIPTION="Ubuntu 16.04.2 LTS"

If your system still is 16.04.1, run the software updater manually and install everything it suggests.

When you have all available upgrades, check that your kernel is in fact held back with the following command:

erik@erik-xps ~ $ uname -r 4.4.0-75-generic

If your kernel version is lower than 4.8 and you are experiencing hardware related issues (like my problems with the WD15), you may very well benefit from a kernel upgrade. The easiest way to do that is to enable something called the hardware enablement stack that instructs your system to install the latest kernels and X version. A warning might be in place, once enabled your system is basically going to get new kernels every time Ubuntu has a new point-release. So whenever 16.04.3 is released your kernel is most likely going to be upgraded again. Getting a new kernel every now and then might be too risky for some systems. Your mileage may vary. My reasoning is that since the XPS 13 9630 is still very new hardware (in Linux terms), new kernels will gradually make it better and better so I accept the small risk that some kernel along the line could potentially mess things up.

To get the hardware enablement stack, I issued the following:

erik@erik-xps ~ $ sudo apt install --install-recommends xserver-xorg-hwe-16.04

A few minutes and a reboot later, my laptop was working better with the WD15 than it did before the devestating 4.4.0.75 upgrade that started this whole mess.

The downside right now seem to be that I get no sound at all from the WD15 now. Neither the audio jack at the front or back seem to be working. Hopefully something that can be resolved but compared to no support for external monitors, a minor issue.

Power cycling the laptop AND the WD15 fixed the audio issue.

Update 2017-04-28:

After getting automatically upgraded to the latest Kernel (4.4.0.75) this week I had a proper sh*t storm of issues with my external monitors for two days. Sometimes they wouldn’t switch on after a cold boot. Sometimes I see the Ubuntu login screen on the external monitors for a second or two before they switch off. Sometimes the external keyboard and mouse wouldn’t work after boot. Even the screensaver would start messing with the external monitors and keyboard, everything was basically random but with a strong bias towards not working at all.

I gradually tracked it down to being an issue with the WD15 dock and its usb-c connection. Some searching around led me to this thread on the Dell Community forums that made me realize I’m running an outdated BIOS, I had version 1.0.7 but the current version is 1.2.3 . I downloaded and updated the the new bios and after 1-2 hours of running, a lot of dock/usb-c related issues seems to be fixed. I recommend every user to use an updated BIOS, but if you’re using an usb-c dock with your Dell XPS, I’d say this BIOS update is mandatory.

New update: I spoke too soon, most of the issues remain the same.

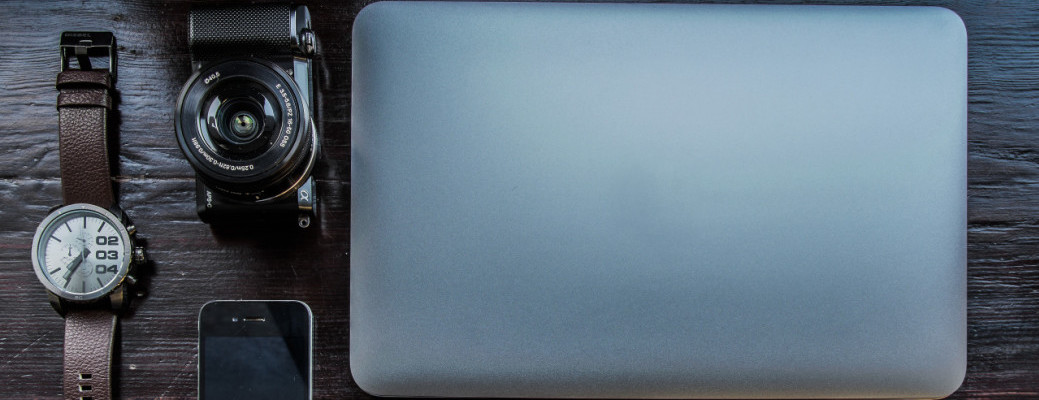

New daily driver

This week my new daily driver arrived. A brand new Kaby Lake Dell XPS 13 Developers Edition (late 2016) that comes with Ubuntu pre-installed. It’s the first time in good number of years that I’m working with latest gen hardware and it’s also the first time I try a laptop with manufacturer support for Ubuntu. Interesting indeed. I also purchased a Dell WD15 dock to hook it up to my 2 22″ screens in the home office.

Apart from a few “paper cuts”, I just love this laptop. It’s the first time ever that I own a laptop with more than 6 hours of (realistic) battery life out of the box. The screen is gorgeous and the backlit keyboard feels really comfortable. If you’re looking for a high end laptop to run Linux, I highly recommend this one.

But as I said above, there are a few annoying things that needs to be improved. This blog post is my way of documenting the changes I’ve made so far and it’s very likely that I keep expanding this post as I discover and hopefully fix issues.

Touchpad

This laptop comes with a really nice trackpad. But when the computer first boots, it will have two separate trackpad drivers active. This makes synclient (the software that controls trackpad configuration) all confused and attach to the wrong driver. The trackpad will mostly work, but it’s not going to be possible to disable the trackpad while typing. This in turn means that if you enable “tap to click” on the trackpad, you will accidentally move the cursor around by “tapping” the trackpad with the palm of your hand driving you insane very quickly.

The solution is a two step process:

Install touchpad-indicator

touchpad-indicator is a utiility that sits in the upper right hand indicator area in Unity. This util gives you some additional configuration settings for the touchpad, “disable touchpad on typing” being the important one for me.

To install it:

$ sudo add-apt-repository ppa:atareao/atareao $ sudo apt-get update $ sudo apt-get install touchpad-indicator

After installing it, I had to start it manually once, and then tell it to autostart on it’s General Options tab.

$ /opt/extras.ubuntu.com/touchpad-indicator/bin/touchpad-indicatDisable the unneeded touchpad driver

Before touchpad-indicator can work, I also needed to disable the unnedded touchpad driver, the third answer in this thread explains how it’s done: https://ubuntuforums.org/showthread.php?t=2316240

Edit: Another thing that might improve the touchpad is to enable PalmDetect, I haven’t played around with it enough to know if it matters or not, but I have to add a line int a X11 config file to enable it:

$ sudo nano /usr/share/X11/xorg.conf.d/50-synaptics.conf

And then after line 13 i added ‘Option “PalmDetect” “1”‘

WD15 Dock

There’s a lot to say about the Dell WD15 dock. For the most part, it works as expected but there are some annoying buts that goes with it. From researching online I realized that with the Linux kernel that comes with stock Ubuntu 16.04 a lot just works and for that I’m thankful. The poor customers that tried to make this dock work with previous versions of Ubuntu have suffered much more than I have. There are a few things that doesn’t work though.

Audio

The WD15 has a 3.5 mm loudspeaker jack on the back that doesn’t work and an similar 3.5 mm headphone jack on the front that does. Not a huge deal for me, I still get decent quality sound to my external speakers, but the installation could have been prettier:

The other annoying thing with the dock is that I have a ton of trouble making it understand when to enable the external monitors, when to wake up from suspend and what resolution to use. I’ve had similar issues with other docks (HP) in the past. I don’t have a solution for it, I guess I just slowly adjust to a lot of rebooting and manual screen resolution management.

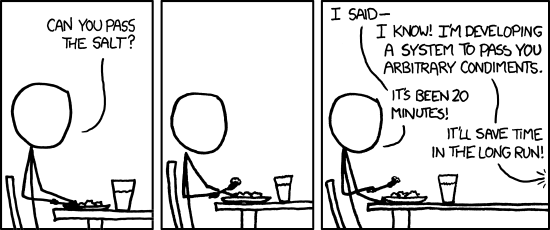

The super key

One of the most odd things with this laptop is that the pre-installed Ubuntu 16.04 comes with a Dell specific package named dell-super-key. This package seem to do just one single thing: disable the super key. If you’re the least bit familiar with Ubuntu, you know that the super key used a lot so exactly what the product developers at Dell was thinking is a mystery to me. Why?

Anyway, it’s easy to fix. Just uninstall the dell-super-key package and you’re good to go.

$ sudo apt-get remove dell-super-key

Conflicting keyboard mapping

I’m not sure if this is specific to the Dell installation of Ubuntu or not but I haven’t had this issue on any other laptops, including my last HP that was also running 16.04. I work a lot with different works paces and I use Ctrl+Alt+Up/Down to move between them. On this one, there was a conflict in mapping so that the Ctrl+Alt+Up combo was also mapped to “Maximize horizontally”. Whenever I had focus on a window that could be maximized, Ctrl+Alt+Up would maximize that window instead of taking me to the work space I wanted.

Searching around in the standard places for where to fix this turned up nothing. I disabled the maximize action in every place I could think of; System Settings -> Keyboard -> Shortcuts as well as using the dconf-editor. Turned out to be the Compiz plugin “Grid” that caused the problem. I solved it by simply disabling these keyboard mappings from Grid.

First, install the Compiz settings tool:

$ sudo apt-get install compizconfig-settings-manager

When install, launch it and search for the Grid plugin:

Then in the Grid settings, click to disable and then re-enable the Grid plugin, it will detect the keyboard mapping conflicts and ask you how to resolve them. I told Grid to not set any of the keyboard shortcuts that conflicted with the “Desktop wall” plugin. That way I can keep some of the Grid features I like, such as maximizing a window by dragging it to the top of the screen:

Conclusion

Compared to 10 yeas ago when I first started using Linux as my primary OS, the tweaks needed to make this laptop work as I want it are minimal. Linux and Ubuntu have come a long long way since then and it’s world of difference.

It would be easy to point a a finger at Dell for shipping a laptop with these issues, but I think that would be very unfair, instead I applaud them for sticking to their Developer Edition program. Sure, the super key thing is weird and perhaps they could have solved the touchpad thing better, but those are solvable. I prefer Dell to keep assembling great hardware, after all, there’s a great community of Linux users around to get the last few issues resolved.

If you have any questions or if you’ve found another Ubuntu and Dell XPS related issue, please use the comment field below.